CHIASM, 1 JOHN 2:3-5

Explaining the Chiasm

Before delving into the chiasm, let’s consider something John said about eternal life, a subject of persistent discussion in the Christian conversation and widely considered to begin for the believer upon death and ascension to heaven. Turning to John 17:3, we read the words of Jesus spoken to His Father: “This is eternal life, that they may know You, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom You have sent.” Jesus’ words form a definition of eternal life–to know the one, true God and Jesus Christ, whom He sent. The key words here are “is” and “know.” What is (estin) eternal life in the words of Jesus found in John 17:3? It is to know the one true God and the one He sent, that’s it. This is expressed in the present tense. Absent here, though not necessarily elsewhere, are any references to faith, heaven, the afterlife, salvation, etc.[1]

Now let’s move back to the epistle of the author, John, in which we find our chiasm. Our task is the chase down the connection between knowing God and eternal life. To explain the chiasm, we begin with a question. How, according to John, do we know that we know God, and His Son, Jesus? The word know, found in all three verses, derives from the root, ginosko. Knowing someone in the sense of ginosko, is a relational term pointing to an experiential form of knowing, personal and very intimate. It corresponds to the Hebrew, yada. “Now the man knew (yada) his wife, Eve, and she conceived and bore Cain.” (Gen. 4:1a) “Adam knew (yada) his wife again, and she gave birth to a son, and named him Seth.” (Gen. 4:25a) In pondering whether to reveal His plans against Sodom to Abraham, the LORD said: “Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do. . .for I know (yada) him, so that he may command (tsavah) his children and his household after him to keep (shamar) the way of the LORD by doing righteousness and justice.” (Gen. 18:17b, 19a) This last verse speaks of the intense, personal relationship between the LORD and Abraham in which the LORD knew him (or in many translations, chose him) to keep (shamar) the way (derek) of the LORD by doing (asah) righteousness (tsedakah) and justice (mishpat). In this last example, knowing the LORD is intimately and inextricably connected to doing what He tells you to do.

We see two words from Genesis 18 that repeat in our verses from 1 John 2, know and keep. A third word, tsavah, meaning command in Genesis 18:19 and the verbal root of the noun, mitzvah, corresponds to the Greek entolas in verses 3 and 4. In our verses from 1 John 2, verse 3 parallels verse 5. In verse 3, we find that by keeping His commandments (entolas/mitzvot) we know that we know God and His Son whereas in verse 5 we know we are “in Him” if we keep His word. The Greek word for “keep” is tereo, literally meaning to guard or watch over. This corresponds in the Septuagint, the earliest Greek translation of the OT, to the Hebrew shamar, the very same word found in Genesis 18:19.

Those who know God do what He says. Verses 3 and 5 repeat this idea and point to the center of the chiasm in which John states that he who claims to know God and Jesus–he who claims an intimate relationship with Them, but does not “keep His commandments,” is a liar–“the truth is not in him.” What then does John mean by truth?

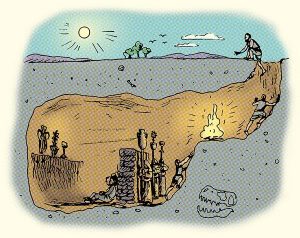

The Greek for truth is aletheia. Again, using the Septuagint as a guide for translation, aletheia translates the Hebrew word emet. It may translate it, but it may not be quite the same as it. The Greek conception of truth pertains to forms and ideas, and in that conception the “form” is the reality, the essence of a thing. What we see in the physical realm is merely a shadow of the real form. Plato uses the example of slaves in a cave.  They sit there in chains, unable to turn their heads, facing a wall. Behind them on a ledge are puppets in front of a fire. The light of the fire casts shadows of the puppets on the wall. The slaves believe the shadows to be the real puppets. Only by unshackling themselves and climbing up upon the ledge would they see the real puppets–the truth. Truth in this conception exists only in the realm of the unseen as an idealization of the shadows we on the ground see. It is a static form, an unchanging state of being. It exists outside us rather than living in us.

They sit there in chains, unable to turn their heads, facing a wall. Behind them on a ledge are puppets in front of a fire. The light of the fire casts shadows of the puppets on the wall. The slaves believe the shadows to be the real puppets. Only by unshackling themselves and climbing up upon the ledge would they see the real puppets–the truth. Truth in this conception exists only in the realm of the unseen as an idealization of the shadows we on the ground see. It is a static form, an unchanging state of being. It exists outside us rather than living in us.

Emet points to something vastly different than this. It is dynamic, not a static form, something that is at work, both in shaping the world outside us, and the character within us. It is not a proposition or doctrine about something or the essence of something or the ideal form of something; rather, it is something we do. The ancient Jewish sages made an observation about the last three words of Genesis 2:3 which in Hebrew reads, bara elohim la-asot. Translated literally into English it would read, “God created to do.” To do what? They noted that the last Hebrew letter of each word–aleph, mem and tav–taken together spelled emet. Therefore, they concluded, God created the world to do truth. Emet, that is, truth, was something God did, and man was created in His image and likeness to do the same. The truth, given by God to man through His words/commands, was considered to be living inside man, maintaining the work God had done on the Earth all the while building his character from the inside out.

Hence, when John, a Hebrew, states in verse 4 that “the truth is not in him,” this is so because such a man is not doing the truth, that is, he is not keeping the commandments of God. He isn’t doing what God has commanded him to do. Unlike Abraham, he is not keeping the way of the LORD by doing righteousness and justice, building his character upon those pillars. John characterizes the character of such a man as a liar–a false and faithless person. Since he is not doing truth, he does not know God. Doing truth–that is, keeping the commandments–is the fabric of our relationship with God.

And now, we circle back to eternal life. Every time we do a commandment of God, we make contact with the eternal. We live our lives through eternal instructions, words that do not fade away. We put truth into action. We enter eternal life in the here and now.

[1] This is not to diminish the connection between faith, the afterlife, salvation and eternal life. For instance, the same author, John, in his gospel quoted Jesus as saying: “For this is the will of My Father, that everyone who beholds the Son and believes in Him will have eternal life, and I Myself will raise him up on the last day.” (John 6:40) The word translated as believes is pisteuon, meaning trust, also a word denoting a close, personal relationship between God and man.

I like the way you put it:

“Emet points to something vastly different than this. It is dynamic, not a static form, something that is at work, both in shaping the world outside us, and the character within us. It is not a proposition or doctrine about something or the essence of something or the ideal form of something; rather, it is something we do.”

“Doing truth–that is, keeping the commandments–is the fabric of our relationship with God.”

One of the great statements I’ve read in a while.